Opinion | Sandra Day O’Connor Never Stopped Being a Politician

In her opinion for a bare five-justice majority, she relied heavily on a pair of amicus briefs. One was by a group of major corporations, led by General Motors, that argued, in Justice O’Connor’s words, “the skills needed in today’s increasingly global marketplace can only be developed through exposure to widely diverse people, cultures, ideas, and viewpoints.” The other brief came from a group of retired military leaders, including H. Norman Schwarzkopf. “Based on decades of experience,” the military leaders, later quoted by O’Connor, argued, “a highly qualified, racially diverse officer corps is essential to the military’s ability to fulfill its principle mission to provide national security.”

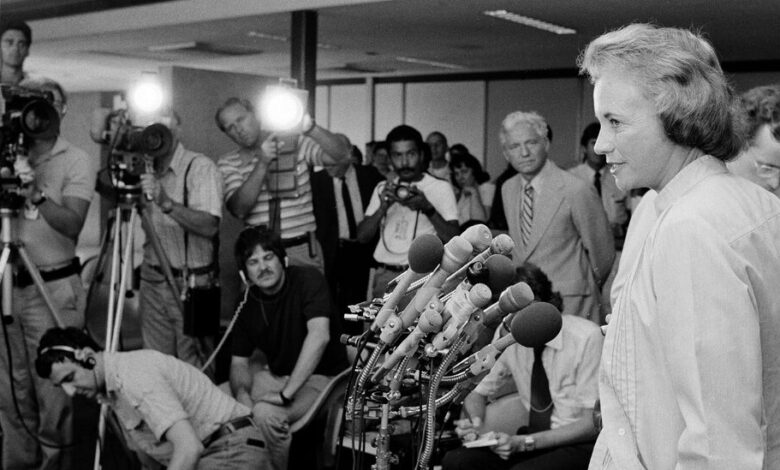

Those people and institutions — roughly, the American establishment — were always Justice O’Connor’s real constituency. Because she was a skilled politician, her radar was set for the political center, and that’s where she always wanted the court to be. On affirmative action, as in the Grutter case, she was in favor of the use of diversity as a factor in admissions but she was against the use of quotas. On abortion, the most contentious issue of her long tenure on the bench, she steered a similar course. In Planned Parenthood v. Casey, from 1992, it looked as if the case demanded a final up-or-down decision on the fate of Roe v. Wade, which was then only 19 years old as a precedent.

Justice O’Connor avoided such a dramatic choice. Instead, she joined with Justices Anthony Kennedy and David Souter in limiting Roe but not overturning it. She upheld restrictions on abortion, like waiting periods, but she would never have voted for an outright ban. And where Justice O’Connor was on the issue is almost exactly where public opinion was, too. In the Casey decision, she did vote to invalidate one portion of the Pennsylvania law, the part that said married women who were seeking abortions first had to inform their husbands. Justice O’Connor didn’t call herself a feminist, though she was one, and the patronizing nature of that provision appalled her. (A lower court judge named Samuel Alito wanted to uphold that part of the law.)

In the period when Justice O’Connor dominated the Supreme Court because she was so often the swing vote, roughly from 1992 to 2005, the court’s major decisions reflected public opinion with great precision. She supported the death penalty, but with limitations; she believed in latitude for the power of the presidency, but not too much; she first supported, then opposed, the criminalization of gay sex (like much of the public, she changed her mind about this.). To her law clerks, her favorite term of opprobrium was “unattractive.” She didn’t want to look bad in front of the public, and she wanted to protect the court from looking that way, too.

As it happens, throughout the court’s history, backgrounds like Justice O’Connor’s were more the rule than the exception. For example, on the court that decided Brown v. Board of Education, in 1954, only one justice had served as a federal judge. (Chief Justice Earl Warren was governor of California; three others had been senators.) They had led big, complicated lives where they had to deal with, and to please, wide varieties of people.