The Vienna Philharmonic’s First Female Concertmaster Helps the Music Flow

On a recent evening at the Vienna State Opera, the robust, singing tone of the violinist Albena Danailova shadowed the melodies of the character Rodolfo in a signature aria from Puccini’s “La Bohème.” Between numbers, she casually chatted with fellow members of the house orchestra before angling her bow and steering the ensemble.

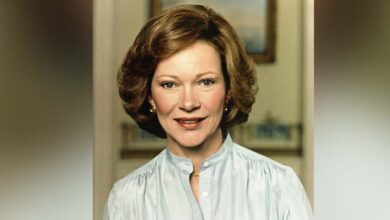

It was just another night on duty. Except that Ms. Danailova, 48, is the first female concertmaster in the history of the Vienna Philharmonic.

She assumed the role in 2011, three years after beginning as a player in the orchestra of the State Opera. (Philharmonic musicians play in the pit for three years before having the opportunity to become an official member.) The Bulgarian native maintains a busy schedule including chamber music activities and coming concerts under conductors including Kirill Petrenko and Herbert Blomstedt. Next Saturday to Monday, she will take the stage of the Musikverein for performances of the annual New Year’s Concert, which will be conducted by Christian Thielemann.

In an interview at the Vienna Philharmonic’s office at the Musikverein, Ms. Danailova observed that recent awareness of gender disparity among orchestra players and conductors had allowed women to feel “more encouraged” and “trust themselves more.”

She noted that the increasing sense of equality has also heightened competition. “Even more than in the past, one’s achievement is what counts,” she said. “Because when the doors are open to everyone, the question is: Who is the best?”

The Vienna Philharmonic first initiated female players in 1997 and since has regularly added women to its roster (the violinist Lara Kusztrich and the clarinetist Andrea Götsch are the most recent recruits). Currently, 24 of the orchestra’s 145 members are women. In the orchestra’s academy, on the other hand, a training ground for young musicians, women hold eight of the 13 seats.

The majority of orchestras in Europe and beyond have yet to achieve full gender equality. For example, a study of 129 publicly funded orchestras by the German Music Information Center in March 2021 revealed that only 21.9 percent of concertmaster positions in Germany were held by women, and that female players overall represented under 40 percent of seats. In the United States, the proportion is higher, around 47 percent, according a report this year from the League of American Orchestras that examined the period from 2014 to 2023.

“There have been English queens for over 200 years,” Ms. Danailova pointed out. “And they were authoritative enough to lead with incredible success.”

However, she said, her position is less like that of a queen than that of the captain of a soccer team. “My role consists of leading but also coordinating, reassuring or challenging, depending on the situation,” she said. “As an intermediary between conductor and orchestra, one has to hold the doors open for the music in the best possible way.”

The Vienna Philharmonic’s chairman, Daniel Froschauer, said that Ms. Danailova was never content to rest on her laurels. He in particular praised the quality of her sound. “That is the essential thing for a concertmaster,” he said. “Everything else can be learned.”

He also pointed to her ability to express emotion in just a few notes: “Her vibrato is very intensive and perfectly suited to opera. Often short solos are the most difficult because one has very little time to capture a mood.”

Ms. Danailova made her professional start in the orchestra of the Bavarian State Opera in Munich, where she began as second violinist and made her way through the ranks to first violinist and then concertmaster. The audition for that ensemble took place right after she had completed her studies with the Romanian violinist Petru Munteanu in Hamburg and Rostock, Germany, in 2001. She never imagined that it would be successful.

“I had enough competitions behind me, but not auditions,” she said. “I wanted to try it out and thought I would return to north Germany.”

She began her violin studies as a young child in Sofia, Bulgaria, where there is a strong tradition of training soloists but less of an infrastructure for orchestra life. “I learned a very flexible, open way of playing in my home country, so that it is possible to integrate different styles,” Ms. Danailova said. “But I never played in an orchestra because I was too young, and there is not a tradition like in Germany or Austria.”

Upon arriving in Vienna in 2008, she steeped herself in local musical traditions — among other things, playing the dance music of the Strauss family in chamber music ensembles in preparation for the New Year’s Concert. “It is a huge challenge because we play this very specific music only once a year,” she said. “There are only three or four rehearsals. And it has to be self-explanatory.”

Ms. Danailova identified a constant tension between music that is immediately associated with Vienna and the vision of a visiting guest conductor. “They come with their own ideas about how this music should be played, and there are of course many pieces to address in little time,” she said. “One above all has to find the right character, articulation, tempo, structure — so that everything unfolds as if the conductor had always led this music.”

“One could explore this for an entire lifetime and never finish,” she continued. “But the performance has to seem thoughtless. It is a combination of harmonious opposites.”

For Ms. Danailova, it is all the more vital to preserve traditions such as playing polkas and waltzes with the right touch of authenticity in a digital age in which countless recordings are available, but there is not always quality control. “It is important that we can provide a kind of natural access to music,” she said. “Not to overplay something, but also not to put it in a museum. To find a golden mean that is organic.”

The violinist pointed out that the Philharmonic had preserved its signature sound even more than other orchestras because it works only with guest conductors rather than engaging a music director. “The orchestra learns a great deal from itself,” she said. “My older colleagues have demonstrated things to me not by speaking but in the way that they play and interpret.”

Having served in the orchestra for more than a decade and, since 2020, as a professor at the University of the Performing Arts in Vienna, she is now in a position to pass on that knowledge to the younger generations. “They have to have an open heart, be interested in the history here, read books and let things seep in,” she said of the Viennese tradition. “It is a reciprocal process. It doesn’t work with force.”

Ms. Danailova pointed to the human voice as the best metaphor for playing string instruments, a concept that continues to nourish the orchestra as it moves between the pit of the Vienna State Opera and the stage of the Musikverein. “A singer has perhaps the best instrument in the world,” she said. “We can integrate that into our sound and vice versa.”

And gender is not the deciding factor. “Either one can play on a high level in all areas that this position demands,” she said of her role as concertmaster. “No matter how one does it.”