Hochul Proposes Paid Prenatal Leave in NY to Make Childbirth Safer

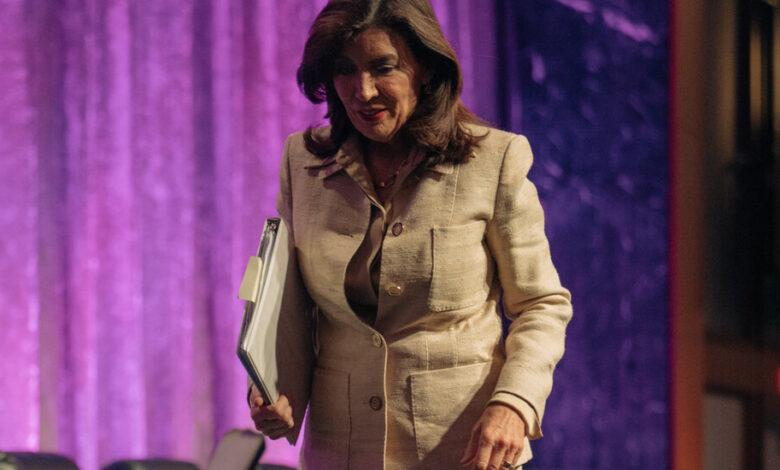

Gov. Kathy Hochul on Thursday announced a series of proposed initiatives to address maternal and infant death in New York, including a proposal that would make the state the first to provide paid leave for prenatal care.

The announcement comes as New York City has been trying to reverse troubling rates of life-threatening emergencies related to childbirth. The risks are especially stark for Black women in the city, who are nine times more likely to die from pregnancy or childbirth than their white counterparts.

Statewide, Black women are over four times more likely to die from childbirth-related complications, according to state data from 2016 to 2018. Nationwide, the rates of infant mortality are increasing for the first time in decades, Ms. Hochul said.

“Mothers and babies are dying unnecessarily across the nation, and right here in New York,” Ms. Hochul said. “This could only be called a crisis. And as the first mom governor, this is personal.”

To address the problem, Ms. Hochul, a Democrat, is proposing a six-point plan to improve maternal and infant health, which would include the elimination of co-pays for pregnancy services, expanded access to doulas statewide, training for clinicians on maternal mental health and free cribs for low-income parents.

The proposal is part of the governor’s annual State of the State plan, in which she lays out her priorities for the legislative session, which began on Wednesday. Ms. Hochul will formally present her vision on Jan. 9, in the Assembly chamber. Like a majority of her proposals, this one would require the support of the State Legislature.

Dr. Christina Pardo, the director of the women’s health practice at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell hospital, called the paid prenatal leave proposal “important,” adding that the lack of such leave “has definitely been a barrier.”

But experts note that the factors contributing to maternal mortality run deep and reflect broader racial and economic inequities and disparities.

“There is no such thing as a quick fix,” said Dr. Pardo, who used to deliver babies at the SUNY Downstate medical center in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, a predominantly Black neighborhood that has one of the city’s highest rates of maternal morbidity.

In New York City in 2020, there were 29 deaths related to pregnancy and childbirth, according to a recent report by the city’s health department. Of those women, 12 were Black, nine were Latina, four were Asian and four were white.

Dr. Pardo noted that chronic diseases like hypertension and diabetes make pregnancy riskier, and are more prevalent among Black and Hispanic adults than white adults in New York City. The overall prevalence of diabetes has soared over the past 30 years. To reduce maternal mortality, she said, “we can’t just focus on the pregnancy time period.”

Ms. Hochul’s proposal does little to address another factor that contributes to the disparities in maternal mortality: the varying quality of medical care across hospitals. In New York City, Black women tend to deliver at hospitals with worse safety records than those where white women deliver. That factor alone might account for nearly half of the racial disparity in maternal morbidity rates in New York City, according to research.

In Brooklyn, for instance, Woodhull Medical Center has emerged as a symbol of the city’s maternal mortality crisis. In November, a 30-year-old mother, Christine Fields, died there from hemorrhaging after giving birth following an emergency C-section, according to the medical examiner’s office. Previously, an anesthesiologist at Woodhull was investigated for botching epidurals. One woman, a 26-year-old first-time mother named Sha-Asia Semple, died in 2020, according to a state medical review board.

Woodhull is part of the city’s public hospital system and about 85 percent of women giving birth there are Black or Hispanic.

The governor’s marquee initiative would make 40 hours of paid leave available to pregnant women to allow them to attend medical appointments. Access to prenatal care can be crucial in making sure pregnancies and births go well.

There are some options already available to women who need to take leave before the birth of their children: New York offers short-term disability during the final weeks of pregnancy, but that can only be used after a seven-day waiting period. Federal leave is also available but it is unpaid. And any leave women take before birth is subtracted from the time available to them to take off after birth — time that can be used for healing and bonding with their children.

Ms. Hochul’s proposal, which is similar to one offered in Washington, D.C., would expand the state’s existing paid family leave policy to include the prenatal period. Under that policy, New Yorkers receive 67 percent of what they would earn at work, up to a weekly cap of $1,151.16.

Politicians in New York City have also sought to address maternal mortality through a range of funding and legislative proposals.

Antonio Reynoso, the Brooklyn borough president, directed his entire capital budget for a year — some $45 million — toward efforts to improve maternal health at Brooklyn’s three public hospitals, which include Woodhull. In 2022, Mayor Eric Adams signed seven maternal health bills that promised more education and more doulas.

The laws were billed as a turning point: the first city legislation to address disparities in maternal mortality, and, as Council Speaker Adrienne Adams put it, “a significant step in our city’s efforts to begin addressing this long overdue issue.”