Power of Black agency something to celebrate

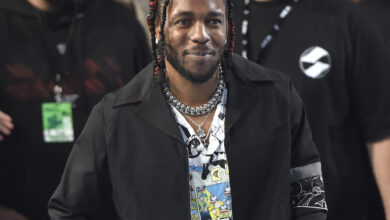

In this Dec. 13, 1964, file photo, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and his wife Coretta Scott King, dance at the Malmen Hotel in Stockholm, Sweden where he was a guest of honor on the one year anniversary festival for the Republic of Kenya. Three days earlier, Dr. King received the Nobel Peace Prize. Back in the U.S., the author writes, tickets to an integrated dinner in Atlanta to honor King for his Nobel were not selling, until Coca-Cola execs threatened to move the company out of Atlanta. (AP Photo/Reportagebild, File)

A few years ago, a photographer gathered Black business owners at the Bruce Bolling Building for a picture. Seeing the number of people there, both men and women, it occurred to me that we should get together more often, not for a photo op, but for networking — to try to do more business with each other. Perhaps we could start by meeting once a year and eventually have more frequent gatherings. Maybe we could make it part of an event such as the Black Economic Council of Massachusetts’ (BECMA’s) annual Mass Black Expo conference . The idea resurfaced when I recently attended Embrace Boston’s annual Sneaker Gala with 1,300 others at Big Night Live.

Both collective and self-efficacy came to mind when I saw Black community members there along with their white and Jewish allies, both individuals and corporations. I concluded that together, we could do anything. We could vote anyone in or out of office, pass any legislation, or advocate for any budget item.

We could take on any issue, such as the shootings in our neighborhoods, which is often the leading cause of death for Black males between the ages of 18-24. Some could help change the “no snitching” attitude. Some could work with the police to make sure they live up to their motto of “To protect and serve.” Some could work to ensure full funding for our community groups offering youth programming, while others could work with our houses of worship to help our youth with issues of identity and purpose and to pick them up when they fall. Others could work with the schools to make sure no student falls between the cracks. Finally, some could work as mentors, volunteers, or good neighbors helping children or families who need family support. We could ensure every one of our children has a bright future and nothing or no one could stop us.

We could help move those in our community from welfare to work with dignity, purpose, and a livable wage.

We could help ensure our returning citizens are ready to reintegrate.

We could improve the quality of education our children receive in their schools, and just as others have organized to remove books, ban the teaching of critical race theory (which means the teaching of Black history), and eliminate diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives in their war against the “woke agenda,” we could demand just the opposite.

Working together, we founded Black colleges and universities, built Black Wall Streets, created the Harlem Renaissance, passed civil rights legislation, and elected and reelected the first Black president. We can and should focus our collective efficacy on creating more equity through our own actions and by encouraging our allies to add their efforts. We should study Black history, AND we should focus on making it.

Yet, look at the voter turnout in Black neighborhoods, the number of parents showing up for parent-teacher night, the number of those who have bought into the “no snitching” philosophy, and those who participate in neighborhood associations, faith-based organizations, and civic engagements involving everything from police reforms to health care disparity and gentrification. Black leaders in Boston have civic, social, religious, political, and economic power and yet, I couldn’t tell you what Boston’s Black agenda is. What are our goals, as a people, what are we trying to achieve?

Our efficacy comes not from the white conservative philosophy of pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps but from Black power and the principles of Kwanzaa. The “white man’s burden” philosophy would have us stay dependent on a paternalistic majority-white society for welfare, employment, education, housing, health care, and justice. Some Black people have accepted this; others have capitulated after fighting a losing battle. It doesn’t have to be that way.

It might not be possible for one individual alone to make changes, but as a tribe, we can do it. This is consistent with the thinking of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Minister Malcolm X. In their 1967 book, “Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America,” Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton defined Black power as “a call for Black people in this country to unite, to recognize their heritage, to build a sense of community” and “to define their own goals, to lead their own organizations.”

There is no issue or agenda item important to the Black community that we can’t change for the better. That’s efficacy, and that’s what we need to work on in Boston’s Black community.

The Sneaker Gala reminded me of the power of our allies — those who provided sponsorship and those who joined us in the room. In 1964, tickets to an integrated dinner in Atlanta to honor King for his Nobel Prize were not selling. Fearing embarrassment, Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr. approached Robert Woodruff, the former president of Coca-Cola, who in turn spoke to then-Coca-Cola CEO J. Paul Austin. Austin, who had seen firsthand how apartheid hurt the economy in South Africa, threatened to take his company out of Atlanta if the city’s elite did not step up. The tickets quickly sold out after that.

The collective efficacy of the Black community in partnership with our white and Jewish allies is indeed a powerful combination and it was on display at the Embrace’s Sneaker Gala.

I wondered what the Rev. King would have thought if he and Coretta had been at Embrace Boston’s Sneaker Gala thrown in his and his wife’s honor — he in a tux and she in a gown and both wearing Air Jordans. I imagine he would have celebrated everyone’s accomplishments, had a few drinks, danced, shaken hands, given a few hugs, and had more than one discussion about how to use the power in the room to take on the next big issue in the fight for equity.

Ed Gaskin is Executive Director of Greater Grove Hall Main Streets and founder of Sunday Celebrations.