Issue 1: Why Ohio’s Abortion Ballot Question Is Confusing Voters

Volunteers canvassing in favor of a ballot initiative to establish a constitutional right to abortion stopped Alex Woodward at a market hall in Ohio to ask if they could expect her vote in November.

Ms. Woodward said she favors abortion rights and affirmed her support. But as the canvassers moved on through the hall, she realized she was not sure how to actually mark her ballot. “I think it’s a yes,” she said. “Maybe it’s a no?”

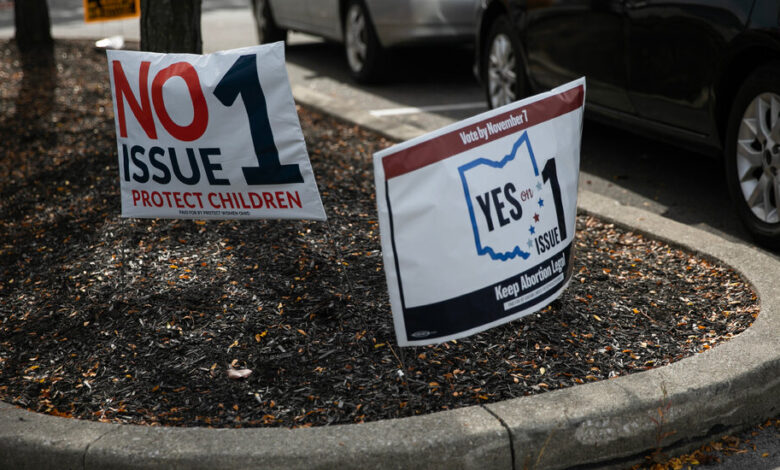

Anyone in Ohio could be forgiven some confusion — the result of an avalanche of messaging and counter-messaging, misinformation and complicated language around what the amendment would do, and even an entirely separate ballot measure with the same name just three months ago. All this has abortion rights supporters worried in an off-year election race that has become the country’s most watched.

But the measure in Ohio is their toughest fight yet. It is the first time that voters in a red state are being asked to affirmatively vote “yes” to a constitutional amendment establishing a right to abortion, rather than “no” to preserve the status quo established by courts. Ohio voters have historically tended to reject ballot amendments.

Republicans who control the levers of state power have used their positions to try to influence the vote, first by calling a special election in August to try to raise the threshold for passing ballot amendments, then when that failed, by using language favored by anti-abortion groups to describe the amendment on the ballot and in official state communications.

Anti-abortion groups, which were caught flat-footed against the wave of voter anger that immediately followed the court overturning Roe, have had more time to sharpen their message. They have stoked fears about loss of parental rights and allowing children to get transition surgeries, even though the proposed amendment mentions neither.

Democrats nationally are watching to see if the outrage that brought new voters to the party last year maintains enough momentum to help them win even in red states in the presidential and congressional races in 2024. And with abortion rights groups pushing similar measures on ballots in red and purple states next year, anti-abortion groups are hoping they have found a winning strategy to stop them.

“Certainly, we know that all eyes are on Ohio right now,” said Amy Natoce, the spokeswoman for Protect Women Ohio, a group founded by national anti-abortion groups including Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America to oppose the amendment.

With early voting underway since mid-October, the state is a frenzy of television and social media ads, multiple rallies a day and doorknobs laden with campaign literature, with each side accusing the other of being too extreme for Ohio.

A “yes” on Issue 1, a citizen-sponsored ballot initiative pushed largely by doctors, would amend the state’s constitution to establish a right to “carry out one’s own reproductive decisions,” including on abortion.

The amendment explicitly allows the state to ban abortion after viability, or around 23 weeks, when the fetus can survive outside the uterus, unless the pregnant woman’s doctor finds the procedure “is necessary to protect the pregnant patient’s life or health.”

But that language does not appear on the ballot. Instead, voters see a summary from the Secretary of State, Frank LaRose, a Republican who opposes abortion and pushed the August ballot measure to try to thwart the abortion rights amendment. That summary turns the provision on viability on its head, saying the amendment “would always allow an unborn child to be aborted at any stage of pregnancy, regardless of viability.”

Other Republicans have helped spread misinformation about the amendment. The state attorney general, who opposes abortion, issued a 13-page analysis that said, among other claims, that the amendment could invalidate a law requiring parental consent for minors seeking abortion. (Constitutional scholars have said these claims are untrue. And the amendment would allow some restrictions on abortion.)

The ballot measure Republicans put forward in August trying to make this one harder to pass was also called Issue 1. Across the state, some lawns still have signs up from abortion rights groups urging “No on Issue 1.”

Abortion rights groups have reminded voters of the consequences of Ohio’s six-week abortion ban that was in effect for 82 days last year — and could go into effect again any day, pending a ruling from the state’s Supreme Court. They repeatedly mention the 10-year-old rape victim who traveled to Indiana for an abortion after doctors in Ohio refused to provide one because of the ban.

In a television ad, a couple tells of their anguish when doctors told them at 18 weeks that a long-desired pregnancy would not survive, but that they could not get an abortion in Ohio, forcing them, too, to leave the state for care: “What happened to us could happen to anyone.”

The “yes” side has also appealed to Ohioans’ innate conservatism about government overreach, going beyond traditional messages casting abortion as critical to women’s rights. John Legend, the singer-songwriter and Ohio native whose wife, Chrissy Teigen, has spoken publicly about an abortion that saved her life, urged in a video message, “Issue 1 will get politicians out of personal decisions about abortion.”

The “no” side makes little mention of the six-week ban, or abortion. Yard signs and billboards instead argue that a “no” vote protects parents’ rights. Protect Women Ohio has spread messages on social media and in campaign literature claiming that because the amendment gives “individuals” rather than “adults” the right to make their own reproductive decisions, it could lead to children getting gender transition surgery without parental permission — which constitutional scholars have also said is untrue.

The anti-abortion side is trying to reach beyond the conservative base, and it will have to in order to win. In polls in July and October, 58 percent of Ohio residents said they would vote in favor of the amendment to secure abortion rights, and that included a majority of independents.

Kristi Hamrick, the vice president of media and policy for Students for Life, which opposes abortion and has been “dorm knocking” on college campuses in Ohio, said the anti-abortion side had relied too much on “vague talking points” to try to win earlier ballot measures. “It wasn’t direct in what was at stake and how people would be hurt,” she said. “What is at stake is whether or not there can be limits on abortion, whether we can have unfettered abortion.”

In Ohio, the anti-abortion side has leaned into arguments that the amendment would encourage “abortion up until the moment of birth.” An ad aired during the Ohio State-Notre Dame football game featured Donald Trump warning, “In the ninth month, you can take the baby and rip the baby out of the womb of the mother.”

Data shows late-term abortions are rare and usually performed in cases where doctors say the fetus will not survive. In Ohio, there were roughly 100 abortions after 21 weeks of pregnancy in 2020.

National groups have poured in money, making this an unusually expensive off-year race. Ohioans United for Reproductive Rights, the coalition of abortion rights groups supporting the amendment, has spent $26 million since Labor Day, nearly three times as much as Protect Women Ohio, and most of that money has come from outside the state.

At the market hall, the group of pediatricians leading the canvass for the “yes” side landed mostly on people who had heard about the amendment and supported it.

One voter, Ashley Gowens, introduced herself to one of the doctors as “Stephanie’s mom,” thanking him for “standing up for my daughter’s rights.” Ms. Gowens worried that abortion rights supporters would be misled by the language on the ballot, or not realize they had to vote again — and differently — after the August election called by Republicans. “I know that it was done purposefully,” she said. “The only way they could knock this down was to confuse people.”

David Pepper, a former state Democratic Party chair, said he too feared the August election had sapped some energy, and that the anti-abortion messages against extremism will appeal to Ohioans’ reluctance to change their Constitution.

“You kind of have to run the table on your arguments, and they all have to be pretty persuasive for people to vote yes,” he said. “All you have to do to convince someone to vote “no” is give them one reason.”