More Than 100 Years Later, Army Overturns Convictions of 110 Black Soldiers After 1917 Houston Riots

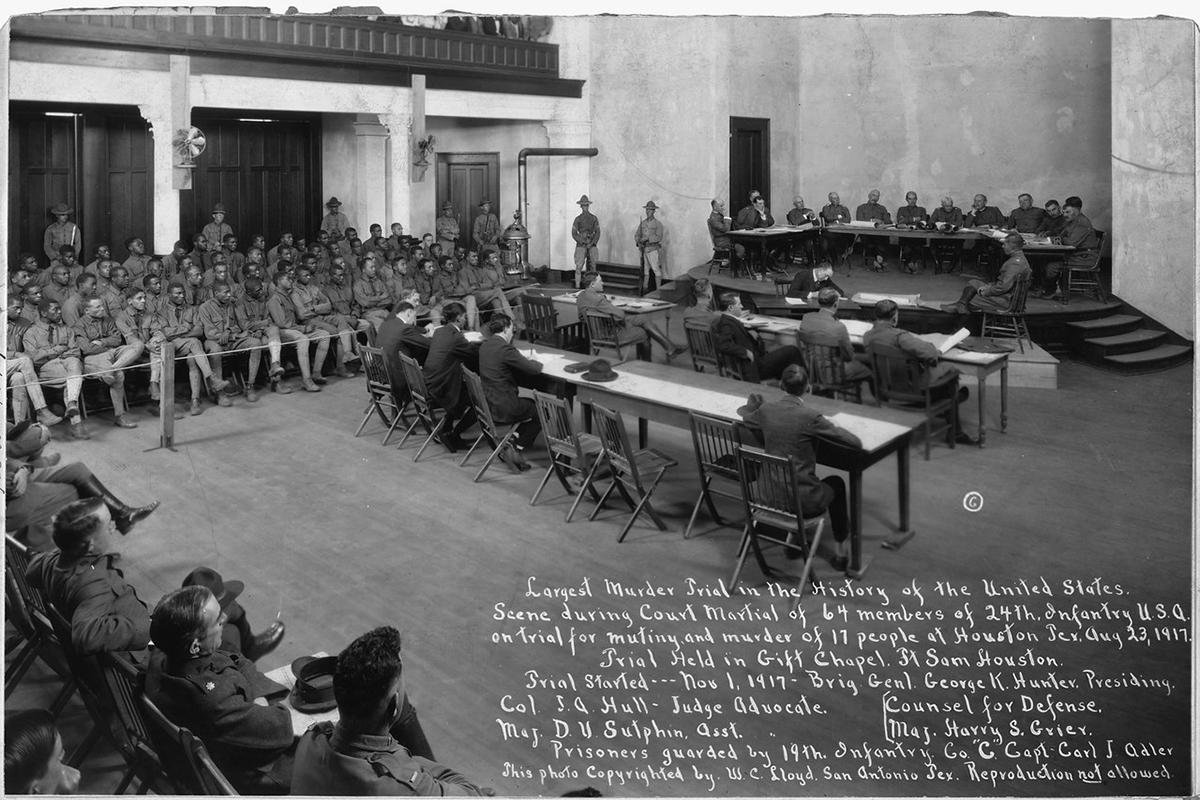

The Army overturned the convictions of 110 Black soldiers charged with mutiny, assault and murder after the 1917 “Houston Riot” — a deadly fray spurred by racial tension in Jim Crow Texas that saw more than 100 troops march from their camp into the city after police pistol-whipped and shot at a Black corporal.

The ensuing trial was the largest in military history and resulted in more than 60 life sentences and 19 hangings of Black soldiers from 3rd Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment, for mutiny. An initial 13 of those hangings were the largest mass execution of American soldiers by the U.S. Army in its history.

In a ceremony Monday at the Buffalo Soldier Museum in Houston, Army officials said that, after historians found many “irregularities” in the way the charges were leveled, the convictions were vacated and the records of the service members will now reflect honorable discharges.

Read Next: Army Identifies 5 Special Operations Soldiers Killed in Black Hawk Crash in Mediterranean Sea

Their descendants, some of whom were in attendance, may also be eligible for Department of Veterans Affairs benefits that were not afforded to those who were convicted.

“The Army has worked very hard throughout its history to acknowledge mistakes and to correct them to become a better institution,” Under Secretary of the Army Gabe Camarillo said Monday. “It’s that ongoing process of learning and growth that brings us here today.”

Third Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment, is a storied unit that was established in the wake of the Civil War in 1866. Soldiers in the unit fought in Cuba, Mexico and the Philippines — “and with their own hands, helped to build the American West,” Camarillo said.

“Even as they faced discrimination from their own country, they fought very hard to protect it,” Camarillo said.

Historian John Haymond and retired military officer and law professor Dru Brenner-Beck co-authored the petition that was recommended to the Army Board for Correction of Military Records. Many of 3-24th’s descendants, including Professor Angela Holder, were instrumental in upholding their honors.

“The work on uncle’s behalf has brought me 109 new uncles,” said Holder, who is related to Cpl. Jesse Ball Moore, one of the 19 hanged. “And I am proud of and love each and every one of them.”

All 110 names of those convicted were read at the ceremony. Some descendants told the crowd that the effort to restore honor had been ongoing for decades.

After the U.S. entered World War I, soldiers with 3rd Battalion were ordered to Camp Logan to guard a construction site along the Houston Ship Channel, according to the Texas State Historical Association.

There, the Black soldiers were subjected to discrimination and racism associated with the Jim Crow South — mandated segregation of public facilities that became rampant after the Civil War.

“The soldiers came to town with patriotism in their hearts, ready to serve their country faithfully,” Brig. Gen. Ronald Sullivan, chief judge with the U.S. Army Court of Criminal Appeals, told the crowd Monday. “But [they] were met with racist provocations and physical violence.”

Police officers often abused Black soldiers in town and — despite being in uniform — they were subject to slurs and mistreatment from white residents, Military.com previously reported when it was learned that the convictions were under review last year.

On a hot August day in Houston and after weeks of racial discrimination, two police officers arrested a Black soldier for interfering with the arrest of a Black woman. Cpl. Charles Baltimore, a military police officer, inquired about the arrest of the soldier, and after heated words were exchanged, the officers pistol-whipped the corporal and shot at him.

Word quickly spread to Camp Logan, though through the rumor mill it was reported back to the camp that Baltimore had been killed and a white mob was on its way.

“Racially motivated incidents, rumors, threats spurred a group of more than 100 Black soldiers to seize weapons and leave camp, thinking that they were marching in their own self-defense,” Camarillo said.

Nineteen people, including four Black soldiers, were killed. Months later, represented by a single officer who was not yet an attorney, the Black soldiers stood trial, Camarillo said. After nearly a month, a court took two days to deliver the first of 58 convictions, resulting in 13 soldiers being hanged. Within a year, 52 more convictions and six more executions followed.

“Even then, the Army recognized the grave injustices that it had perpetrated on its own soldiers,” Camarillo said, adding that the then-War Department made it so that death sentences must go through presidential review. The trial also laid the foundation for review processes that carry on in today’s Uniform Code of Military Justice.

A descendant of Pfc. Thomas Hawkins, Jason Holt, an attorney, also spoke and read the names of the first 13 service members who were hanged after being convicted.

“From the families of those executed to all of you, nothing — nothing — can replace what we lost. The worth of their lives is not found on a sheet of paper,” Holt said. “Taking their 20s, their 30s, their 40s, their 50s and so on cannot be replaced — that is lost forever in an ultimate abyss of what if.

“But today is in truth a day of atonement … for the Jim Crow-era South and legalized segregation,” he said.

“Today, a mortal blow has been dealt to the injustice of the master-slave relationship, such that 106 years later, the color of their skin was not a barrier to the fair dispensation of military jurisprudence, and we all here rejoice that their convictions were overturned and set aside.”

— Drew F. Lawrence can be reached at drew.lawrence@military.com. Follow him on X @df_lawrence.

Related: How a Race Riot Involving an Army Unit Led to the Largest Murder Trial in US History